Epic Mossack Fonseca breach tied to basic patch management failures

Coverage of the widely reported disclosure of thousands of documents from law firm Mossack Fonseca has emphasized details the use of legal and financial structures that can and apparently have been used by many high-profile individuals to conceal assets or avoid taxes and the public identification of some of the firm’s more famous or noteworthy clients. Initial media reports characterized the disclosure as a “leak,” at least in part because the firm’s activities came to light when an anonymous individual approached a reporter at German newspaper Suddeutsche Zeitung and offered to provide a large volume of documentation (so large that the work of examining it required the involvement of hundreds of journalists coordinated through the International Consortium of Investigative Journalists). Although the identity of the source who provided this trove of documents has still not been made public, subsequent technical analysis of the situation and of Mossack Fonseca’s website and client portal strongly suggest the data was exfiltrated by an external hack, not by an insider acting as a whistleblower. More astonishing, at least from an information security perspective, is that the hack apparently exploited well-known vulnerabilities in open-source software tools that Mossack Fonseca used. If the results published by security investigators are accurate, then the Mossack Fonseca breach might have been avoided had the firm simply performed routine patching and updates on its website and portal technology.

Mossack Fonseca uses the popular WordPress platform for its website and the open-source Drupal content management system (CMS) for its client portal. Unpatched security vulnerabilities in both toolsets appear to have contributed to the hack, as an out-of-date WordPress plugin may have enabled the compromise of the Mossack Fonseca website and its email system, while exploits of an unpatched Drupal server appear to have left the MF client portal vulnerable to a flaw with a known exploit so critical that Drupal users were warned back in October 2014 to assume that any unpatched servers had been compromised. According to multiple security researchers, including some cited in reporting on the Drupal problem by Forbes, based on server information stored on (and publicly accessible from) the MF portal the site continues to run a version of Drupal rife with exploitable vulnerabilities.

The irony in all this is that law firms globally take client privacy very seriously, holding fast to attorney-client privilege protections in many countries and generally working to keep private transactions and business dealings, well, private. In the face of all the unfavorable press, Mossack Fonseca was quick to claim that many critics fail to understand the nature of its activities on behalf of clients, and even the journalists who worked long and hard to identify MF clients and their offshore holdings have not established that anything Mossack Fonseca did for those clients is actually illegal. More investigations on that front seem to be ongoing, as numerous media outlets reported just today that Mossack Fonseca’s Panama offices had been raided by local authorities, presumably seeking evidence of illegal activities. Cynical observers (and security analysts) might counter that Mossack Fonseca failed to understand even basic information security and privacy principles and lacked the IT management skills or oversight necessary to ensure that they were adequately protecting their own and their clients’ information.

MedStar attack apparently enabled by unpatched software

When news broke at the end of March that MedStar Health, a large hospital operator in the metropolitan Washington, DC area, had shut down its computer systems in response to a malware attack, initial speculation on the cause of the infection reflected a general assumption that one or more of the company’s 30,000 employees must have fallen victim to a phishing scam. Numerous reports by the Washington Post and other major media outlets cited information provided by unnamed hospital employees as evidence that the MedStar network had been hit with a ransomware attack, in which data files are encrypted by attackers who offer to provide a decryption key in return for payment. Neither MedStar nor law enforcement agencies investigating the attack have confirmed that ransomware was involved; instead, official MedStar statements emphasized the work being done to bring systems back on line and fully restore normal operations.

Hospitals and other health care organizations are often assumed to have relatively weak security awareness and training programs for their employees, raising the likelihood that a clinical or administrative staff member might fail to recognize a suspicious link or email attachment and unwittingly introduce malicious software. The HIPAA Security Rule requires security and awareness training for all personnel working for covered entities (and, thanks to provisions in the HITECH Act extending security and privacy rule requirements, to business associates too) but HIPAA regulations do not specify the content of that training so it is up to each organization to make sure their training covers relevant threats. The HIPAA security rule includes “procedures for guarding against, detecting, and reporting malicious software” within its standard for security awareness but here too offers no practical guidance on how organizations should protect themselves against malware.

About a week after the attack occurred, Associated Press reports published by the NBC affiliate serving Washington, DC attributed the MedStar attack to the successful exploitation of an unpatched vulnerability in a widely used application server technology. The vulnerability in JBoss software components incorporated in multiple products from Red Hat and other large vendors was disclosed in 2010 and has been fixed in versions of software products released since that time. Despite the widespread availability of patched versions of the software, systems in many organizations remain vulnerable. This exploit is targeted by a specific ransomware attack (known as Samas or samsam) that has been around for more than two years and, as recently as last week, has been seen with increasing frequency by security researchers. Unlike many other types of ransomware that rely on phishing to compromise systems and spread, attackers who find vulnerable JBoss servers can deploy Samas without any action on the part of users in the targeted organization. The implication of the Associated Press report is that the MedStar attack was in fact ransomware, although by all indications the organization chose to recover its systems and data from backups rather than pay to remove the encryption presumably put in place by the attack.

OPM (finally) notifies people affected by breach

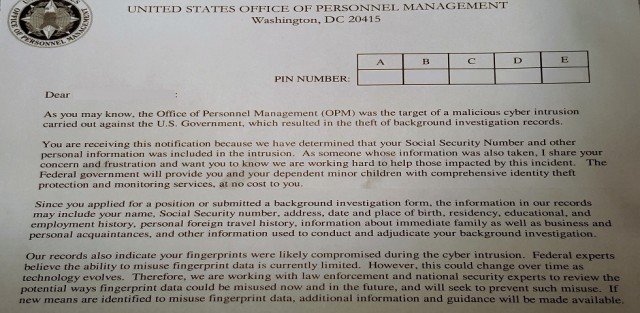

On June 9, 2015, the U.S. Office of Personnel Management (OPM) publicly announced the results of a computer forensic investigation – initiated many months earlier – indicating that background investigation records on as many as 22 million individuals had been compromised in a long-term intrusion into the agency’s computer systems. As noted in the OPM press release, it discovered the security incident resulting in the breach in April, and after further analysis determined that unauthorized access to OPM personnel and background investigation records had begun nearly a year earlier, in May 2014. It’s not entirely clear why OPM waited almost two months to publicly disclose the breach, but affected individuals have had to wait much longer to receive notification from OPM confirming their information was among the compromised records. OPM first had to hire a contractor to help it conduct the notification campaign and provide support to affected individuals, so it did not start sending notifications until the beginning of October. Given the large number of recipients, it should come as no surprise that the notification process has been drawn out; my letter from OPM arrived on November 23, 137 days after the public announcement and approximately 200 days after OPM says it discovered the incident.

The significant time lag associated with notification is troubling on several fronts, at least for those affected by the breach, but the simple fact is that there are no regulations or guidelines currently in force that compel OPM or any other federal agency to act faster on its notifications. All U.S. federal agencies are required, under rules issued by the Office of Management and Budget in May 2007 in Memorandum M-07-16, to notify the U.S. Computer Emergency Readiness Team (US-CERT) of “unauthorized access or any incident involving personally identifiable information” within one hour of discovery. The OMB rules do not specify an explicit notification timeline, but do say that notification should be provided “without unreasonable delay” following the discovery of a breach. After the recent series of large-scale breaches of personal information by private sector entities, the Obama Administration and both houses of Congress have proposed legislation that would, among other things, impose strict notification timelines for data breachs. As part of a broader set of initiatives intended to protect consumers, the Administration in January suggested a Personal Data Notification and Protection Act that, like the Senate’s version (S. 177) of the Data Security and Breach Notification Act, would require breach notification within 30 days. The House version (H.R. 1770), introduced three months later than the Senate’s bill, shortens the notification deadline to 25 days. None of these pieces of legislation have been enacted but even if they had they would presumably not bind OPM or other federal agencies, because they are intended to introduce statutory provisions enforced by the Federal Trade Commission that apply to entities that fall under FTC authority. It’s difficult to understand why government agencies should be continue to make their own definitions of what constitutes an “unreasonable delay” if commercial and non-profit organizations are to be expected to notify breach victims within 30 days.

The significant time lag associated with notification is troubling on several fronts, at least for those affected by the breach, but the simple fact is that there are no regulations or guidelines currently in force that compel OPM or any other federal agency to act faster on its notifications. All U.S. federal agencies are required, under rules issued by the Office of Management and Budget in May 2007 in Memorandum M-07-16, to notify the U.S. Computer Emergency Readiness Team (US-CERT) of “unauthorized access or any incident involving personally identifiable information” within one hour of discovery. The OMB rules do not specify an explicit notification timeline, but do say that notification should be provided “without unreasonable delay” following the discovery of a breach. After the recent series of large-scale breaches of personal information by private sector entities, the Obama Administration and both houses of Congress have proposed legislation that would, among other things, impose strict notification timelines for data breachs. As part of a broader set of initiatives intended to protect consumers, the Administration in January suggested a Personal Data Notification and Protection Act that, like the Senate’s version (S. 177) of the Data Security and Breach Notification Act, would require breach notification within 30 days. The House version (H.R. 1770), introduced three months later than the Senate’s bill, shortens the notification deadline to 25 days. None of these pieces of legislation have been enacted but even if they had they would presumably not bind OPM or other federal agencies, because they are intended to introduce statutory provisions enforced by the Federal Trade Commission that apply to entities that fall under FTC authority. It’s difficult to understand why government agencies should be continue to make their own definitions of what constitutes an “unreasonable delay” if commercial and non-profit organizations are to be expected to notify breach victims within 30 days.

Individuals affected by the OPM breach have been offered three years of credit monitoring and identity theft protection through ID Experts, an independent commercial firm specializing in these services to which OPM awarded a $133 million contract in September. Recipients of notification letters (there are two versions, depending on whether an individual’s fingerprints may have been included in the breach) can enroll in the MyIDCare service using a 25-character PIN and following a multi-step enrollment process (including an identify verification step using an Experian service, which T-Mobile subscribers in particular might find ironic). The privacy policy associated with MyIDCare identifies not ID Experts but CS Identity Corporation (CSID) as the provider of the identity theft protection service; CSID is essentially a wholesaler reseller of its services to companies like ID Experts. There is little in the privacy policy that is remarkable, although for users of CSID’s services who don’t come to the company via a U.S. entity like OPM, the reference in the policy to compliance with the U.S. – E.U. safe harbor framework seems due for revision. ID Experts’ privacy policy suffers from the same problem, but that is largely irrelevant where the OPM-sponsored services are concerned. Still, individuals affected by the OPM breach can be expected to have an interest in privacy practices of the service provider contracted to ostensibly protect them from future harm (at least for three years), so it is unfortunate that MyIDCare subscribers may potentially be confused by the existence of multiple privacy policies linking back to different corporate entities.

What’s the harm in inaccurate personal information?

On November 2, the U.S. Supreme Court heard oral arguments in Spokeo, Inc. v. Robins, a case that stems from complaints by a consumer (Robins) that Spokeo, an online “people search engine” that aggregates information about individuals from public sources, published inaccurate information about him. The argument before the Court focused on a legal question about whether the standing exists for someone who has not suffered demonstrable “real world” harm to bring a lawsuit against an entity that has violated the law. In this particular case, Robins claims that Spokeo violated the Fair Credit Reporting Act (FCRA) when it published multiple pieces of erroneous information about him. The statutory regulations under the FCRA (15 U.S.C. §1681) require consumer reporting agencies to “follow reasonable procedures to assure maximum possible accuracy of the information concerning the individual” (§607(b)) on which they report. The arguments before the Court neither address nor dispute whether Spokeo is a credit reporting agency (it is, at least for purposes of establishing FCRA jurisdiction over the company) or whether it did, in fact, publish inaccurate information about Robins (it did). Instead, the case centers on whether the lawsuit is allowable at all, since Robins can only point to evidence that Spokeo violated FCRA rules, but cannot show that he suffered any injury or damage because of the mistaken information. Generally speaking, individuals or entities with rights of action related to, for instance, claims of negligence, must prove actual harm in order to bring suit. This is why victims of data breaches are typically unable to sue the companies that lost their data for damages related to things like a increased future likelihood that they will suffer identity theft. Those who actually experience identity theft can sue for damages, but not until they actually incur harm.

The FCRA does include statutory penalties for credit reporting agencies that knowingly violate the provisions in the law, although the limit of liability is capped at $2,500 per violation. The problem for Robins is that the ability to seek these civil penalties rests with the Federal Trade Commission, not with individuals like him who believe (or can provide evidence) of statutory violations. Robins instead has to establish that he even has a right of action, which is the core issue the Supreme Court is considering. The Court has taken up this issue before, including in First American Financial v. Edwards, which the Court dismissed without explanation and without issuing a ruling on the matter of standing, instead simply stating that it should not have taken the case in the first place. The case has drawn attention (and a large volume of amicus briefs on both sides) far beyond the realm of credit reporting, in large part because although there is ample precedent in tort law that plaintiffs need to demonstrate actual standing in order to sue for damages, showing harm has historically not be required for legal standing under the Constitution, particularly when Congress explicitly includes legal remedies for statutory violations. During oral argument, some justices seemed willing to accept that having inaccurate information published about a person could constitute harm, which would allow Robins to proceed with the lawsuit, but sidesteps the key question of standing. What’s unfortunate about this case is that it in no way addresses very real questions about responsibility for the establishment and maintenance of data integrity.

Under FCRA regulations, consumers have the right to dispute information reported by FCRA-covered companies if they believe the information to be inaccurate. In most cases – even with the much larger and better-known major credit reporting agencies like Equifax, Experian, and TransUnion – the reporting entities do not create the information they hold about consumers, but they receive and aggregate information from numerous third party sources. This, perhaps obviously, presents a challenge when the information collected and reported by one of these companies is wrong. The law requires the credit reporting agencies to employ “reasonable procedures” to ensure not only the accuracy and relevance of consumer information, but also its protection from unauthorized disclosure (confidentiality) and its proper use. As originally enacted, consumers who wanted to dispute something in their credit reports had to take the issue up with the reporting agency itself; Congress amended the regulations in 2003 with the Fair and Accurate Credit Transactions Act (FACTA) that enabled consumers to dispute information directly with creditors or other entities that are the source of the information the credit reporting agencies receive and report. The FTC subsequently issued guidelines to entities that furnish information to credit reporting agencies that place a substantial burden on them to report only accurate information. These rules would seem to put the onus on furnishers of information, rather than the credit reporting agencies, since under current regulations the responsibility for providing accurate information rests with the furnishers. It makes sense that a company like Spokeo, if the information it aggregates comes from such entities subject to the FTC regulations, would presume that the information it receives is accurate. It is much less clear in the regulations to what lengths a credit reporting agency must go to demonstrate that it has followed “reasonable procedures” to ensure information accuracy.

Hopes for better privacy protection in CISA depend on conference committee reconciliation

Now that the Senate has passed its own version of the Cybersecurity Information Sharing Act (CISA), work on the legislation shifts to reconciling the Senate bill (S. 754) with similar measures passed by the House of Representatives earlier this year. Privacy advocates and industry groups oppose the new legislation for many of the same reasons that led to the demise of the Cyber Intelligence Sharing and Protection Act (CISPA) in each of the two previous Congresses, but in the wake of a seemingly unending string of major data breaches and cyber intrusions, it appears quite likely that the current Congress will get a bill to the the president for signature. It’s worth noting that while the House did introduce another version of CISPA in February, the House legislation that actually passed – the Protecting Cyber Networks Act (PCNA) (H.R. 1560) – was introduced separately in March and includes much stronger privacy protection language than the Senate’s CISA bill. The best prospects for closing the many privacy loopholes in the Senate version now rest with the House members in the conference committee that, according to CISA co-sponsor Senator Richard Burr, likely will not produce a final bill until sometime in 2016.

Critics of the Senate CISA bill note that it provides few provisions to ensure that personal information of private citizens is not disclosed improperly by companies that voluntarily share cyberthreat information with the federal government. What’s more, CISA would effectively insulate companies that failed to remove personally identifiable information from legal action by preempting the other federal privacy legislation. The House’s PCNA, in contrast, directs the Department of Justice to develop and periodically review privacy and civil liberty guidelines related to cyberthreat indicators and associated information shared with the government, and even affords individuals a private right of action if those guidelines are violated – a provision similar to causes of action in the Privacy Act and several other major privacy regulations now in effect. The CISA bill’s supporters in the Senate have consistently argued that privacy concerns are overblown, noting that cyberthreat information sharing with the government by private sector entities is voluntary, and that the legislation includes provisions requiring the removal of personal information that is not directly relevant to cyberthreat indicaors.

A separate line of criticism has been directed at CISA and other proposed legislation focused on information sharing between private sector entities and government agencies because that legislation includes few, if any, provisions that would actually mandate or strengthen security measures that public or private sector organizations implement to protect personal information or other sensitive data. To be sure, improving the security posture of commercial companies and government agencies across the board is a laudable goal, but there is essentially no precedent in federal security or privacy legislation affecting non-government entities. Both versions of FISMA (the Federal Information Security [Management | Modernization] Act), the Government Information Security Reform Act that preceded FISMA, and the Privacy Act only govern federal executive agencies. Industry-focused laws like the Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act (HIPAA), the Electronic Communications Protection Act (ECPA), and the Graham-Leach-Bliley Act (GLBA) clearly state security objectives but are not particularly prescriptive about how those objectives are to be attained. Under the presidents 2013 Executive Order 13636, Improving Critical Infrastructure Cybersecurity, the National Institute of Standards and Technology (NIST) produced a standard cybersecurity framework that private-sector organizations could use, but the framework is voluntary. It seems neither politically nor commercially feasible that the government could successfully mandate minimum security requirements for private sector organizations, although it might make sense for the government to condition federal cybersecurity assistance given to those entities after an attack on their compliance with such standards.

SecurityArchitecture.com

SecurityArchitecture.com